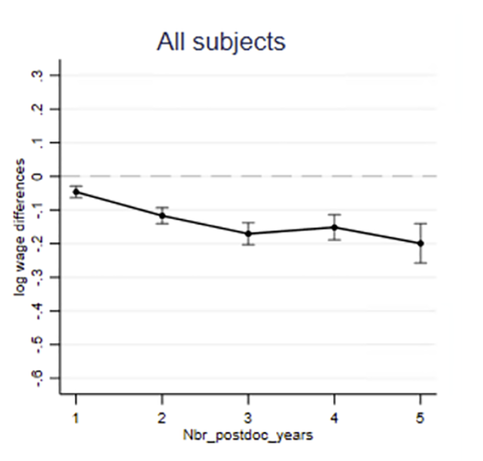

In most cases, doctoral graduates leave universities some years after graduation. How much do doctoral graduates earn when they leave university? Do postdoc years monetary pay off outside academia? In a recent paper, Johannes König shows that postdoctoral time does not result in wage premiums but is associated with wage losses outside academia. Moreover, the later doctoral graduates leave academia, the less they earn in the private sector (in the first five years after graduation). The wage gap is sizable and rapidly grows with postdoc time (see Fig 1). The first postdoc year is associated with a wage loss of 5% compared to no postdoc experience. Leaving five years after graduation is associated with a wage loss of 18%.

Johannes finds this pattern in the labor market, analyzing more than 33 000 observations within an extensive 15 years timeframe (graduates between 1994 and 2009). This pattern holds on the five largest subject fields: humanities and arts, social sciences, science and mathematics, medicine, and engineering. Moreover, these findings "can be considered representative of doctorate recipients who were employed as postdocs at universities for up to 5 years after graduation and later changed the employment sector".

Naturally, the question arises if selection plays a role: Perhaps, the most productive, ambitious postdocs stay in academia, while others leave with no wage premium or loss. Apart from including a set of control variables that can account for the difference between doctoral graduates, Johannes uses a matching approach that shall partially reduce this concern. He matches statistically comparable doctoral graduates on observable characteristics, e.g., age, citizenship, previous work experience, and compares the wages among them. Yet, the pattern remains unchanged after this procedure suggesting the robustness of the observed wage gap.

These results beg the question if one can consider the postdoctoral period as a further qualification used to justify a postdoc's relatively insecure working conditions. Why is the payoff so low if the postdoctoral period is deemed the advanced qualification phase?

Read more:

König, J., 2022. Postdoctoral employment and future non-academic career prospects. Plos one, 17(12), p.e0278091.

Naturally, the question arises if selection plays a role: Perhaps, the most productive, ambitious postdocs stay in academia, while others leave with no wage premium or loss. Apart from including a set of control variables that can account for the difference between doctoral graduates, Johannes uses a matching approach that shall partially reduce this concern. He matches statistically comparable doctoral graduates on observable characteristics, e.g., age, citizenship, previous work experience, and compares the wages among them. Yet, the pattern remains unchanged after this procedure suggesting the robustness of the observed wage gap.

These results beg the question if one can consider the postdoctoral period as a further qualification used to justify a postdoc's relatively insecure working conditions. Why is the payoff so low if the postdoctoral period is deemed the advanced qualification phase?

Read more:

König, J., 2022. Postdoctoral employment and future non-academic career prospects. Plos one, 17(12), p.e0278091.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed